RACISM IN ROMANTIC MUSIC (4): CANONICAL SILENCING, AND SOME CONCLUSIONS

- John Michael Cooper

- Jun 26, 2023

- 5 min read

As a prefatory exercise for this post, consider the “rule of 4%”: less than four percent of the players in professional orchestras with budgets over $1 million in the U.S. are non-White; less (MUCH less) than four percent of the professionally recorded Romantic music is by non-White composers; and less than four percent of the repertoire in the textbooks that are the principal instructional tools of aspiring musicians is by non-White composers. In the world of Classical music, which is dominated by Romantic music of the long nineteenth century, White supremacy has a quantitative advantage on the order of approximately 96% (ninety-six percent).

Such is the power of the canon and the things discussed in Parts 1-3 of this post.

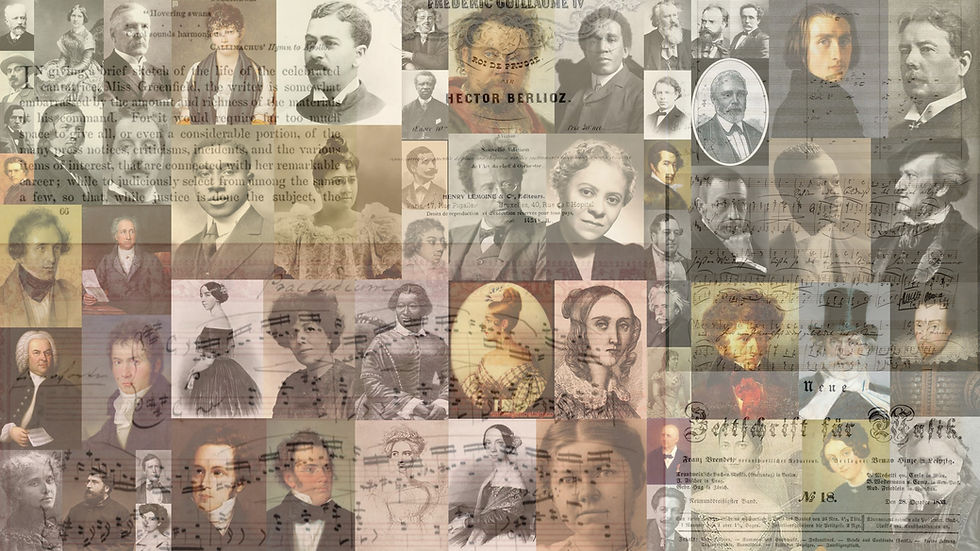

So here’s the final installment. Together, these installments attempt to unpack the omnipresent force of racism in Romantic music (RRM) and something of the means and mechanisms by which it effected not just the intellectual culture, music history, music theory, and performance life of the long nineteenth century, but also the historiography of those things and the ways in which racism – despite its pervasive influence on the worlds of Romantic music – has managed to escape the sort of presence in discussions of nineteenth-century music that is routinely afforded the other -isms of those years. The series as a whole is a systems-level analysis of White Romanticism’s marginalization, sometimes to the point of invisibility, of non-White voices – of how White folk of the long nineteenth century were able to portray Romanticism as a quintessentially White phenomenon in which non-White folk were, in the end, not at home. It also discusses how racist Whites managed to make it so that countless later musicians would see Romanticism (overwhelming evidence to the contrary notwithstanding) as “White” – just as most surveys and studies of nineteenth-century music still do today.

The operative concept in this analysis is linchpin – a locking pin (here, figurative) that serves to hold together parts or elements that exist or function as a unit (here, systemic racism). In Part 1 I discussed the racist linchpin of the intellectual culture that shaped the worldviews of listeners, music historians and theorists, and performers alike. In Parts 2 and 3 I discussed the racist linchpins of the silencing of non-White voices by the music-publishing industry and archives and libraries. And in this installment I discuss the force that that imaginary museum of musical composers and works known as the canon (“rule, law, decree”) works as an intangible, but incredibly potent, exclusionary force that ensures that musical White supremacy will continue to reign as long as we, the community of musicians, allow it to determine what music we know and what music we don’t.

We have a choice, you see: every time we choose to listen to, play, sing, or study a canonical work or composer, in so doing we choose to accept and perpetuate the canon’s silencing of non-White voices. If I choose to write this year's 759,000th blog post on Mozart, I'm choosing to do that instead of writing a much-needed post on Margaret Bonds, Florence Price, Clarence Cameron White, or some other non-White composer whose marginalization is the result of her/his race, not her/his genius and importance. If I did that I'd be choosing to let race privilege win -- choosing racism.

Anyway, a few concluding words follow that discussion of the White-race-privileging canon as agent of racism in Romantic music. Here goes:

***

The fourth linchpin securing the role of racism in Classical music derives from Romantic musical culture’s obsession with the musical canon, for the processes of canon formation have always been directed by the assumptions and values that led 18th- and 19th-century theorists and historians to ignore or disparage non-White Classical composers and their works while celebrating and valorizing White ones.

Put simply, music that is unknown because its sources are not preserved cannot enter the canon. Music that is not performed because performers cannot access it or even know of its existence (see Parts 2 and 3) cannot enter the canon. Music that historians and theorists do not comment on cannot enter the musical canon (ditto); and so on. And because the canon is by definition an exclusionary construct that sacralizes an established received corpus of composers and works, rehearsing and celebrating these endlessly, obsessively while ignoring or only grudgingly acknowledging others, music (including works by non-White composers) that had no chance of entering the canon because of the racist linchpins traced in this entry can exist only in the margins, is tantamount to supporting race privilege (see Part 1). The racist subordination of non-White musics can be righted, and those composers and works canonized, only when performers and writers on music, acknowledging the racism that shaped the Romantic musical canon as it currently exists, collaborate to illuminate the music and musical sources that were Othered and obscured by that racist history and rebuke its ideological assumptions as well as the conclusions to which they led.

Conclusions: The economic, legal, and social structures of the long 19th century affirmed and enacted these four linchpins at every turn. It was not only a matter of the White musical public generally ignoring non-White performers’ renditions of music by Black composers, dismissing or condescendingly criticizing non-White performers’ interpretations of White composers’ music, rebuking non-White performers for singing “White music,” or suggesting that non-White musicians were adopting a White countenance in singing music by White composers (thereby insinuating non-White cultural appropriation of music that was a White prerogative and assuming that the categories of Blackness and Whiteness were mutually exclusive). More than this, Black performers were barred by ordinance and/or law from designated White stages; Black audiences were banned by ordinance and/or law from designated White halls; White concertgoers generally avoided Black and integrated performance spaces; and so on. Worse, Black folk lived ever under the threat of White-on-Black violence for any perceived infraction real or imaginary, violence that would be committed with impunity because the perpetrators were acting in accordance with the law. The threats of arson that attended Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield’s 1853 debut at New York’s Metropolitan Hall, the thrown fruit at Roland Hayes’s Berlin debut, and the beating to which Hayes was subjected while peacefully shopping for shoes in Rome, Georgia were parts, visited on musical luminaries, of the same political landscape that produced race riots, widespread arson, and lynchings from Reconstruction to the late 20th century and the same sociopolitical culture that in the early 21st century nonsensically renders controversial the assertion that “Black lives matter.”

The roots of racism in Classical music spread wide and run deep; the system’s capacity for self-affirmation, self-legitimation, and self-perpetuation is extraordinary. Musicians who are content to perpetuate the system of race privilege and race disparagement – whether this concerns anti-Black racism or some other form of it – will find abundant existing literature, whether aesthetic or critical or historical or theoretical, to rationalize their stance, as well as abundant models for enacting the White racial frame at every level of musical life. Those who reject, or simply wish to think critically about, the White racial frame will find comparatively few models and precedents; they must be prepared to expend massive amounts of time and energy uncovering and mainstreaming the works, musicians, and musical practices whose submersion and marginalization was the goal of the system of White racist dominance in Romantic music. The latter group must also be prepared to see their non-compliance decried as “hating” or “canceling” Beethoven or some other historical beneficiary of race privilege in Romantic music. In the early 21st century this situation is polarized and politically charged, but increased awareness of the pervasiveness and injustice of racism in the musical world has given that charge the ability to address the racist legacies of Romantic music more effectively than before. [JMC]

As noted in Part 1, this material is lightly adapted from my forthcoming Historical Dictionary of Romantic Music, 2nd ed. (Lanham, Marlyland: Rowman & Littlefield). The 794 entries in that dictionary include a number of other entries related to this post (e.g., ANTI-SEMITISM AND ANTI-JUDAISM, EXOTICISM, NATIONALISM, NEW ENGLAND AFRO-AMERICAN SCHOOL; PHILADELPHIA AFRO-AMERICAN SCHOOL; SEXISM AND MISOGYNY). I think I'll share the ANTI-SEMITISM AND ANTI-JUDAISM entry next week.

Your love is the canvas of my life, painted with colors of joy and tenderness 🎨💖. Let’s create a masterpiece together with Delhi call girls, making every stroke a moment to cherish forever 🖌️.