RACISM IN ROMANTIC MUSIC (3): ARCHIVAL SILENCING

- John Michael Cooper

- Jun 25, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Jun 29, 2023

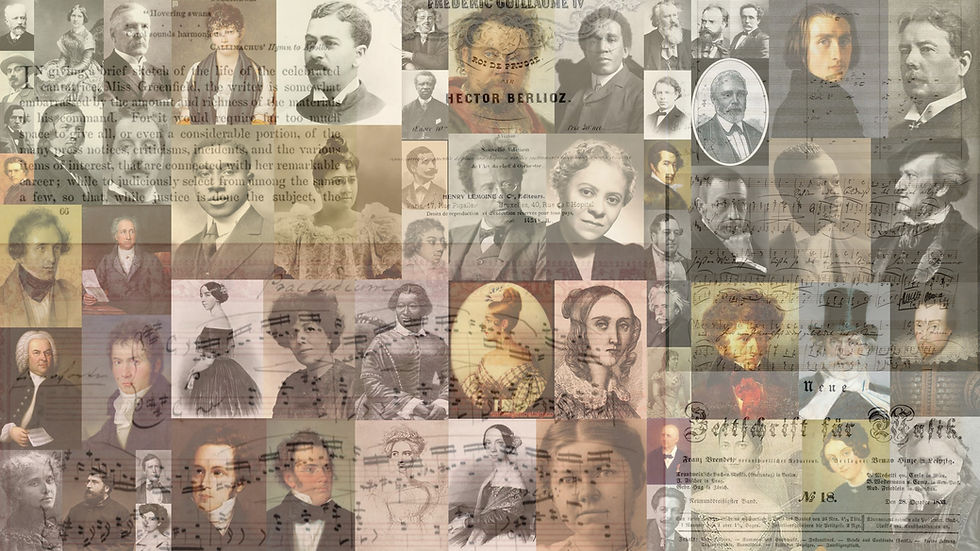

In Parts 1 and 2 of this four-part post I attempted a systems-level analysis of the means and mechanisms (“linchpins”) by which racism saturated the worlds of Romantic music and music historiography while managing to avoid the sort of recognition that is routinely afforded topics such as nationalism, exoticism, organicism, and so on. In Part 1, I focused on the cultural and intellectual facets that helped to create and perpetuate White race privilege in Romantic music (and continue to do so today), and in Part 2 I focused on the agency of music publishers during the long nineteenth century and today in cultivating White race-privilege and Othering non-White composers and music to the point of near invisibility.

In Part 2 I also encouraged you to take steps to counter this systemic culture of White supremacy in Romantic music by seeking music manuscripts in libraries and archives. That was actually a segue into this third installment as well as a genuine encouragement. For the archives and libraries that, as institutions, ought to have preserved the truly vast musical contributions of non-White composers and the documentation of their lives and careers actually devoted their resources overwhelmingly only to White musicians, their lives, their careers. The creative legacies and documents of life and work for non-White musicians were not deemed worthy of archival preservation. The libraries of the institutions now known as HBCUs stepped up valiantly, as did other institutions such as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the Center for Black Music Research at Columbia College (Chicago) – but network of non-White musicians who contributed vitally to the worlds of Romantic music and the creative legacies of these musicians greatly exceeded anything the resources of these dedicated archives could keep up with.

As a result, the prevalence of racist ideology in archives and libraries whose jobs it was to act as stewards of the musical worlds of the long nineteenth century relegated unknowable amounts of non-White music to – in best cases – private collections that are not publicly accessible, and more commonly to landfills. There is no way of knowing what treasures have been lost: Scott Joplin’s lost first opera, A Guest of Honor (1903), is almost certainly one such casualty, but it cannot be the only one and may not be the greatest.

We may never know. That’s the point of this third installment:

The third linchpin of racism in Romantic music (RRM) derives from the historical attitudes of archives, libraries, and museums vis-à-vis the manuscripts, printed editions, recordings, and other sources that collectively document Black Classical musical creativity and Black musical life. These institutions have historically been diligent in collecting and preserving “significant” sources for posterity – but their understanding of “significant” has been determined by the same racist White-dominated educational institutions, historical and theoretical concepts, and musical practices that have historically marginalized non-White musical creativity. Consequently, while virtually every scrap of paper documenting the work of (e.g.) Bach, Handel, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Mendelssohn, Wagner (etc.) has been assiduously preserved and catalogued, during the long 19th century and well beyond few institutions recognized the significance of documents that related to Black music and musicians. (One important exception to this rule was the libraries of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities that began to emerge in the U.S. – but these institutions could not possibly accept or account for the vast musical production of American Blacks during the long 19th century.) As a result, distressingly few publications of Black Romantic music survive and countless manuscripts of unpublished works by Black Romantic composers have been lost: the curatorial stances of White-dominated archives conspired with the political economy of music publishing and the racist values of music historians and theorists to ensure that those musicians would be invisible to posterity, their music inaudible.

***

In Part 4 (here) I’ll discuss the role of canon culture in perpetuating the damage done by the three linchpins discussed so far, then offer a few concluding observations.

Comments