RACISM IN ROMANTIC MUSIC (2): SILENCING BY MUSIC PUBLISHERS

- John Michael Cooper

- Jun 24, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Jun 29, 2023

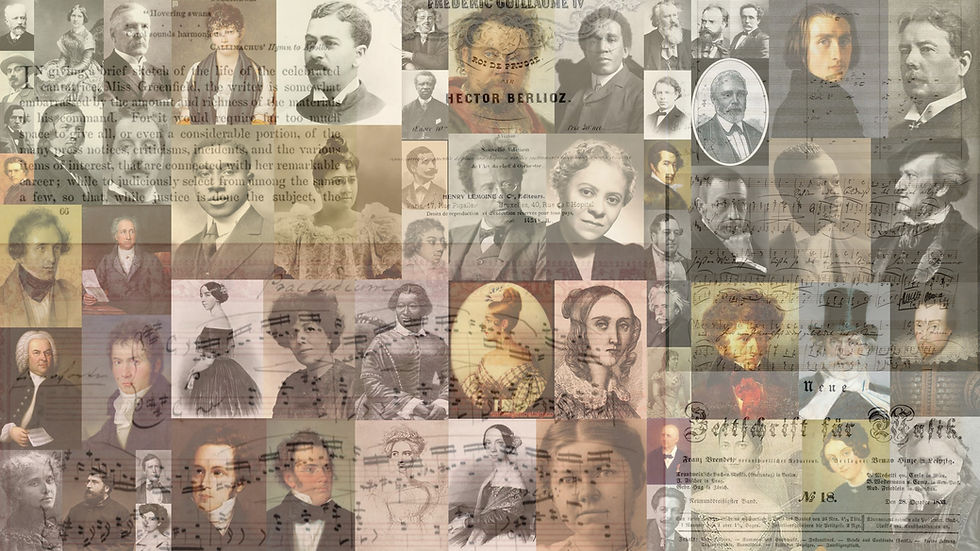

In Part 1 of this series of systems-level commentaries on Racism in Romantic Music (RRM), I discussed how the pervasive racism of the societies in which Romantic musics were born inevitably shaped those societies’ values, ideas in music history and music theory, and their music itself – so that racism, which has never received a dedicated treatment in any survey of Romantic music, is as central or even foundational to the phenomenon of Romantic music as many other topics are that are included in such studies as matters of course (nationalism, exoticism, organicism, etc.). Today I talk about how the music-publishing industry – which was of course owned and operated by persons reared with those same racist worldviews – was able to wield extraordinary power in silencing non-White musical voices because of Classical musicians’ overwhelming reliance on printed and published music.

To check these observations empirically, I suggest the following:

First, review the publication catalogs of one or more music publishers, especially publishers active during the long nineteenth century (although the situation has changed little today). How many scores by non-White composers do you find? (Viewing this as a percentage shows White publishers’ implicit but potent messaging that non-White folk don’t write classical music – at least, not classical music that’s worthy of print and publication).

Your numbers will be something on the order of 96-98%+ White, <4% non-White. If you are happy with this, if you believe that -- despite the historical record of unpublished music by non-White composers -- this is a fair or just statistic, then your work here is done. If you're troubled by that colorasure (another term I borrow from Prof. Philip Ewell), then read on.

If you’re a performer, ask yourself what manuscript music by non-Whites there is for you to sing or play and where you can get it. If you’re a scholar, ask yourself what music there is by non-Whites for you to consider as you think, talk, and – most importantly, in terms of lasting consequence – teach about Romantic music. And ask yourself where you can get it.

If you know where you can get those pieces that the White-dominated music-publishing industry has marginalized to the point of invisibility but haven’t yet done so, it’s time to go to an online catalog of a holding archive or library and order scans. of unpublished music by non-White composers If you don’t do this, you’re tacitly acquiescing to the power of this linchpin, allowing our dependency on printed and published music to keep music by non-White musicians from being a part of the White-dominated worlds of Romantic music.

(And one more side note: this situation has changed despicably little today. When Margaret Bonds tried to get the National Association of Negro Musicians to craft a resolution requiring members to purchase a certain amount of music by Black composers every year, and when she contemplated founding a Black-owned and operated music-publishing company (“Musico Negro”), she revealed her awareness of this extraordinary veto power that musicians seldom recognize because for musicians to think deeply about our reliance on printed and published music would be in some ways akin to fish thinking deeply about water: it is the defining condition of our world.)

Enough. Here are some thoughts on the second linchpin in RRM:

The second linchpin of RRM is that Classical musicians – performers, historians, and theorists alike – overwhelmingly depend on the printing and publication of notated music, a situation that has become more pronounced in the post-World War II era. (Earlier performers were less uncomfortable working from musical manuscripts than more recent ones are.) Published music can be accessed, studied, taught, learned, performed, and heard, but if a musical composition remains in manuscript it can be performed and studied historically or theoretically only by relatively few – generally only during the composer’s lifetime, since composers’ manuscripts typically are either subsumed into estates or donated to libraries after death. In view of Classical musicians’ dependency on printed music, these exigencies often mean that music publishers hold the key to the posthumous as well as contemporary survival or obscurity of musical works. Because the political economy of Classical music publishing, as part of the same White-dominated political economy that generally subjugated non-White peoples, was dominated by White firms during the long 19th century, this circumstance largely ensured that non-White composers’ names and works would enjoy only limited dissemination during their lifetimes and would then become marginalized to the point of obscurity, effectively erased after their deaths. Performers cannot sing or play music they cannot access, theorists cannot work to understand it, and historians cannot incorporate it into their historiographic views and presentations: by these means the race privilege of the White-dominated world of music publishing has silenced the musics of countless Black composers and writers on music, rendering their work inaudible and invisible.

***

Up next in Part 3: Archival silencing (here)

You’re the rhythm of my heart, a beat that keeps me alive and in love 🎶💘. With a call girl in Delhi adding a touch of grace, let’s dance through life’s most romantic moments 🌹.